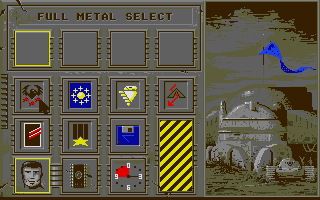

Full Metal Planet Manual Transfer

Patient Slings. Patient Slings 2 Part. Removing/Installing the Metal Support Bars in the Standard Style Sling. TRANSFER ONE-PIECE STYLE SLINGS. On this site you will find the software 'Full Metal Program., your mission is to land your spaceship on a Full Metal Planetand to. The user manual and.

Last updated: April 13, 2017. Have you ever tried pedaling a up a really steep hill? It's pretty much impossible unless you use the right gear to increase your climbing force.

Once you're back on the straight, it's a different story. Flick to a different gear and you can go incredibly fast: you can magically make your turn round much faster than you're pedaling. Gears are helpful in machines of all kinds, not just cars and cycles. They're a simple way to generate more speed or power or send the power of a machine off in another direction.

In science, we say gears are simple. Photo: Typical machine gears. An opened-up gearbox on show at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England. In a car or a motorcycle, the gears 'mesh' so the teeth of one wheel lock into the teeth of another; that stops them slipping, which means power is transmitted more smoothly and efficiently. In a bicycle, the gears don't link by meshing together directly. Instead, a chain connects together the gear wheels (known as sprockets) on the pedal with those on the back wheel.

That's simply because the pedal and the back wheel are some distance apart and a chain is the easiest way to link them together. What do gears do. And how do they do it? Gears are used for transmitting power from one part of a machine to another. In a bicycle, for example, it's gears (with the help of a chain) that take power from the pedals to the back wheel. Similarly, in a car, gears transmit power from the (the rotating axle that takes power from the ) to the driveshaft running under the car that ultimately powers the wheels.

You can have any number of gears connected together and they can be in different shapes and sizes. Each time you pass power from one gear wheel to another, you can do one of three things:. Increase speed: If you connect two gears together and the first one has more teeth than the second one (generally that means it's a bigger-sized wheel), the second one has to turn round much faster to keep up. So this arrangement means the second wheel turns faster than the first one but with less force.

Looking at our diagram on the right (top), turning the red wheel (with 24 teeth) would make the blue wheel (with 12 teeth) go twice as fast but with half as much force. Increase force: If the second wheel in a pair of gears has more teeth than the first one (that is, if it's a larger wheel), it turns slower than the first one but with more force. (Turn the blue wheel and the red wheel goes slower but has more force.). Change direction: When two gears mesh together, the second one always turns in the opposite direction. So if the first one turns clockwise, the second one must turn counterclockwise. You can also use specially shaped gears to make the power of a machine turn through an angle.

In a car, for example, the differential (a gearbox in the middle of the rear axle of a rear-wheel drive car) uses a cone-shaped bevel gear to turn the driveshaft's power through 90 degrees and turn the back wheels. How do they do it? Gears sound like magic, but they're simply science in action!

Look at the diagram on the right and you'll see exactly how they work. The pair of gear wheels (top) works in exactly the same way as an ordinary pair of wheels the same size that are touching (middle); the only difference is that the gears have teeth cut around the edge to stop them slipping. But a is really just a lever, so a pair of wheels that touch is like a pair of levers that touch (bottom). Thinking of gears as levers shows exactly how they work.

Suppose you turn the axle at point (1). The bar connecting points (1) and (2) moves faster and with less force at point (2) because it's working as a lever. If you can't see this, suppose the red bar were a spanner and you pushed at point (2) to undo a nut at point (1) in the center. Then point (1) would turn with less speed and more force.

If you turn at point (1) instead, the opposite is true: you get more speed and less force at point (2). That's the red bar, which is just touching the blue bar. As the two bars touch, they must be going at the same speed. Now the blue bar is also a lever, but it's working the other way: like a spanner. So if we apply a force at point (2), it's magnified by the leverage of the blue bar and we get more force (and less speed) at point (3). Putting everything together, what do we get? We apply a certain force and speed at point (1).

The red bar might give us four times the speed and a quarter of the force at point (2). But the blue bar will work the other way and maybe halve the speed and double the force. So when we get to point (3), we have twice the speed and half the force that we had at point (1). That's what we'd expect from a pair of gear wheels where one (red) is twice the size and has twice as many teeth as the other (blue). Why do we need gears?

Let's think about cars. A car has a whole box full of gears—the gearbox—sitting between the crankshaft and the driveshaft. But what do they actually do? A makes power in a fairly violent way by harnessing the locked in gasoline.

It works efficiently only when the pistons in the cylinders are pumping up and down at high speeds—about 10-20 times a second. Even when the car is simply idling by the roadside, the pistons still need to push up and down roughly 1000 times a minute or the engine will cut out. In other words, the engine has a minimum speed at which it works best of about 1000 rpm. But that creates an immediate problem because if the engine were connected directly to the wheels, they'd have a minimum speed of 1000rpm as well—which corresponds to roughly 120km/h or 75mph. Put it another way, if you switched on the ignition in a car like this, your wheels would instantly turn at 75mph! Suppose you put your foot down until the rev counter reached 7000 rpm.

Now the wheels should be turning round about seven times faster and you'd be going at 840 km/h or about 525 mph! It sounds wildly exciting, but there's a snag. It takes a massive amount of force to get a car moving from a standstill and an engine that tries to go at top speed, right from the word go, won't generate enough force to do it. That's why cars need gearboxes. To begin with, a car needs a huge amount of force and very little speed to get it moving, so the driver uses a low gear. In effect, the gearbox is reducing the speed of the engine greatly but increasing its force in the same proportion to get the car moving.

Once the car's going, the driver switches to a higher gear. More of the engine's power switches to making speed—and the car goes faster. Changing gears Photo: Bicycle gears: Bikes have two sets of different-sized gears on the wheel you pedal and the back wheel.

Instead of touching directly and rotating in opposite directions, each pair of gear wheels is connected by a flexible metal chain (kept taught by a springy lever and gear-shifting mechanism called a derailleur), so they turn in the same direction; technically, gears linked this way are called sprockets. When you change gear, you shift the chain from one pair of sprockets to another.

For cycling at speed, you'll use a larger sprocket on the pedal wheel than on the back wheel. In theory, changing gears is about using the engine's power in different ways to match changing driving conditions. The driver uses the gearshift to make the engine generate more force or more speed depending on whether hill-climbing power, acceleration from a standstill, or pure speed is needed. In practice, changing gears means meshing different sized gear wheels together, but you can't do that while the gearbox is transmitting power from the engine at high speed. That's why you need to press a car's clutch pedal before changing gears, which disengages the engine's input from the gearbox. You can then use the gearshift to change to a different pattern of gears, before letting the clutch transmit power back from the engine to the gearbox (and the wheels) once again.

On a bicycle, it's much more obvious what's going on when you change gears because you can see it happening. As you flick the gear shift, you can watch (and feel) the chain hop from one sprocket to another, engaging different-sized gear wheels. On many bikes, the gear change is controlled by a clever mechanism called a derailleur, which smoothly diverts the chain from sprocket to sprocket even though you're pedaling along at speed. Five different ways to use gears I've made these five simple gear machines with an old construction set to illustrate a few of the ways in which we can use gears to do different jobs.

Gears for speed In this simple gearbox, I've got (from right to left) a large gear wheel with 40 teeth, a medium wheel with 20 teeth, and a small wheel with 10 teeth. When I turn the large wheel round once, the medium wheel has to turn twice to keep up. Similarly, when the medium wheel turns once, the small wheel has to turn twice to keep up. So, when I turn the large gear wheel on the right, the small wheel on the left turns four times faster but with one quarter as much turning force. This gearbox is designed for increasing speed. Rack and pinion gears You've probably seen one of these in cliff- and hill-climbing, but they're also used in car steering systems, and many other kinds of machines as well. In a rack and pinion gear, a slowly spinning gear wheel (the pinion) meshes with a flat ridged bar (the rack).

If the rack is fixed in place, the gear wheel is forced to move along it (as in a railroad). If the gear is fixed, the pinion shifts instead. That's what happens in car steering: you turn the steering wheel (connected to a pinion) and it makes a rack shift from side to side to swivel the car's front wheels to the left or the right. In simple weighing scales, when you load a weight on the pan at the top, it pushes a rack straight downward, causing a pinion to rotate. The pinion is attached to a pointer that rotates as well, showing the weight on the dial. Sun and planet gears If you need to convert reciprocating (back-and-forth) motion into rotation, you normally do it with a and connecting rod; that's how pistons drive the wheels on.

But you can do the same thing with gears. In this arrangement, a small gear called a planet (which, it's important to note, is fixed to a rod so that it cannot rotate) is moved around a second (usually bigger) gear called a Sun. As the rod moves the planet back and forth, the Sun spins around. Sun and planet gears were popularized by James Watt, who was unable to use a crankshaft in his pioneering steam engine because it was originally protected by a patent.

What's the catch? Artwork: Gears can give you more speed, but only by giving less force; they can give more force, but only by giving less speed. This is why a pair of gears can't create energy. With two perfect gears, you'd get exactly as much energy out as you put in; with real gears, friction, noise, air resistance and so on mean you get less energy out than you put in. You might think gears are brilliantly helpful, but there's a catch.

If a gear gives you more force, it must give you less speed at the same time. If it gives you more speed, it has to give you less force. That's why, when you're going up hill in a low gear, you have to pedal much faster to go the same distance. When you're going along the straight, gears give you more speed but they reduce the force you're producing with the pedals in the same proportion. Whenever you gain something from a gear you must lose something else at the same time to make up for it.

If that weren't the case, you could use gears to create and make what scientists call a perpetual motion machine—and that's absolutely forbidden by a law of physics called the. Formally stated, it says that you can't create or destroy energy, only convert it from one form into another.

To put it more informally, as my old physics teacher used to say: 'You don't get 'owt for nowt' or 'There's no gain without pain'! Photo: In an egg whisk, gears help to make light work of mixing in two different ways—by increasing speed and changing direction. When you crank the handle, you turn the large outer gear wheel at moderate speed. This large wheel meshes with a pair of small gear wheels fitted to the top of the two axles attached to the blades. Each rotation of the large wheel (blue) makes the smaller wheels turn round several times (red), giving a dramatic increase in speed at the blades.

Full Metal Planet Pc Game

The gears also help by changing the direction of rotation: you crank the handle about a horizontal axis, but the two whisk blades turn about a vertical axis. Find out more On this website. How to make your own gears.: A simple introduction to making gears from the Instructables website.: Need to draw a pattern for cutting your own wooden gears? Look no further than this handy little page from Matthias Wandel of Woodgears.ca.: Matthias Wandel talks us through the process of cutting wooden gears in this 5-minute YouTube video.

Books for younger readers. by Chris Woodford. Facts on File, 2004. One of my books, this 96-page volume for ages 9–12 charts human efforts to harness the power of the natural world. by Richard Hammond.

Dorling Kindersley, 2007/2015. A light-hearted, fun introduction to the simple physical laws that rule our world. I was a contributor to this book too. Books for older readers. by Ivan R. Special Interest Model Books, 1987.

A clear guide to how to make your own gears in models. by Chris Woodford. Bloomsbury, 2015. I talk about gears in Chapter 4, The Beauty of Bikes, expanding a little bit on the discussion in this article. Articles. by David Schneider. IEEE Spectrum.

Gears get an upgrade into the Arduino age!.: The New York Times, February 13, 2009. An interactive (Flash-based) look at electronic bike gears.

Having the flexibility to shift on the fly from two to four wheel drive without having to get out and lock the wheel hubs is a luxury that most of us take for granted, especially during a snowstorm. Many of today's vehicles are equipped with part time four wheel drive systems, which will engage either manually when the driver selects a switch or automatically when the on board computer senses that wheel traction is reduced by weather or road conditions.

The physical part of the vehicle that activates this action is the transfer case, which has an output shaft that delivers power to the drive axle. From time to time, the seals that connect these components together can dry up, wear out, or break. If this occurs, they will have to be replaced by a certified mechanic sooner rather than later to avoid further damages to the vehicle's drive system. What is the transfer case output shaft seal? The transfer case output shaft seal is located on the transfer case of four-wheel drive cars, trucks, and SUVs.

The transfer case completes the activation between two-wheel drive neutral, to low four-wheel, and then to drive four-wheel. Inside the case are a series of gear reductions and chain drives that work together to accomplish their task of supplying power to the drive axles, making the vehicle four wheel drive. The transfer case output shaft is the part that connects the case to the axle. The purpose of the transfer case output seal is to prevent fluid from leaking out of transmission, where the transfer case is connected by way of the transmission's input shaft. The seal also helps to keep fluid from leaking out of the front and rear output shaft to the differentials, which keeps all metal components properly lubricated for extended use. If the seals leak, fluid escapes and is no longer able to properly lubricate the interior components of the transfer case.

Eventually the parts inside will wear out and. If this happens, the transfer case will be rendered useless and the four-wheel drive operation will not work. The transfer case output shaft seal can fail, and when it does, will display a few symptoms that will alert the driver that a problem with this system exists. Noted below are a few of the common side effects of a. Difficulty shifting gears The seal that keeps fluid inside the transfer case and thus the transmission is vital for the smooth operation of the vehicle's transmission. When from a broken seal, it reduces the volume of fluid that is currently working inside the transmission. A loss in fluid pressure also occurs, which will make for an automatic or manually shifted transmission.

If you notice that your transmission is having difficulty shifting to higher or lower gears, you should contact a certified mechanic as soon as possible to inspect this problem and offer a solution. Grinding noises coming from underneath the vehicle When the output shaft seal breaks or wears out, it also can cause noises to appear from under the vehicle.

Full Metal Planet Wiki

In many cases, these noises are caused by the reduction of lubricants inside the transfer case or metal-to-metal grinding. It's pretty obvious to most vehicle owners that metal grinding together is never a good thing, so if you hear, contact a mechanic as soon as possible. Vehicle jumps in and out of four-wheel drive In some cases the loss of fluid will cause the vehicle to jump in and out of four wheel drive, when it is supposed to stay in this operation.

This is commonly caused by broken parts inside the transfer case that control this operation. The parts become worn out prematurely due to the leaking fluid caused in many cases by the output shaft seal. When the seal leaks, you will notice under your vehicle. This is transmission fluid and an instant sign that a seal or gasket on your transmission case is broken and needs to be fixed. Anytime you recognize these warning signs, it's important for you to contact a professional mechanic so they can as soon as possible.

Comments are closed.